Elastic fantastic

‘Racing is about saving time, in the pits or on the race track.’

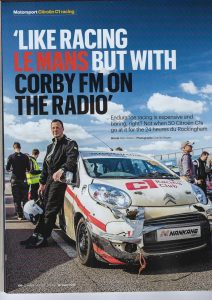

That’s a John Surtees quote and one that Reid lives by. With quite some fervour. He might be quietly spoken, impeccably polite and about the nicest bloke you could meet, but there’s also an obsessive, burning competitiveness that characterises everything he does over the race weekend at Rockingham. Sure, this is grass roots motorsport, but he wants to win just as much as he did when he came third with Porsche at Le Mans in 1990.

The first thing he did was elasticate the seatbelts – using the basic, stretchy white elastic normally found in camping shops, he tied the harness to the cage, so that the belt jumped back out of the way when it was undone. It saves precious seconds during driver changes, as you always know where the belts are.

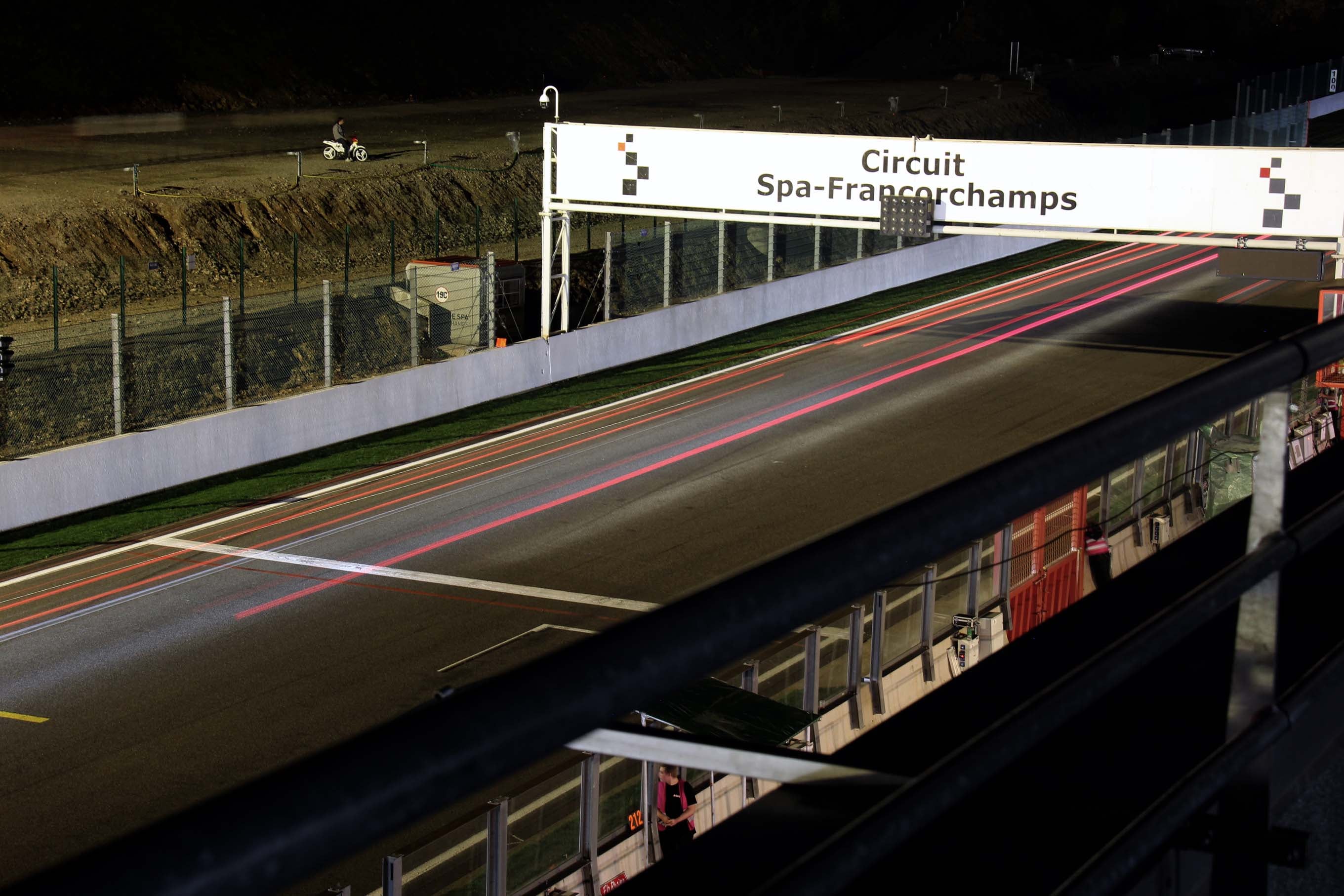

I found out just how good this trick is as I threw myself, deeply terrified, into the car at about 7.30pm. We were in P7 – the same position we’d qualified in. All our testing had happened in dry sunshine and now I was faced with a soaking track, darkness, and a car that had already lost its driver-side mirror.

Still, it was a relief how easy it was to get the belts on since we knew exactly where they were… A nifty, cheap free hack to save you time. Remember that one.

Tyre torture

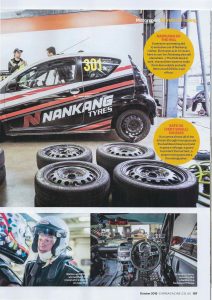

Another of Reid’s major focuses in testing and the run-up to the race is the tyres. The skinny Nankang tyres cost around £20 a corner, and are of course obligatory in the series. Box-fresh from the factory, they’re then shaved down (still leaving plenty of tread, mind), which makes them rather less grippy.

Reid is tireless (if you’ll excuse the pun) in figuring out the best pressures and how worn they should be in order to achieve the best times. We make sure that all of the tyres are scrubbed with a few progressively harder laps so that they are race-ready but honestly, the monsoon weather makes much of that redundant.

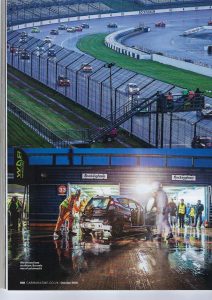

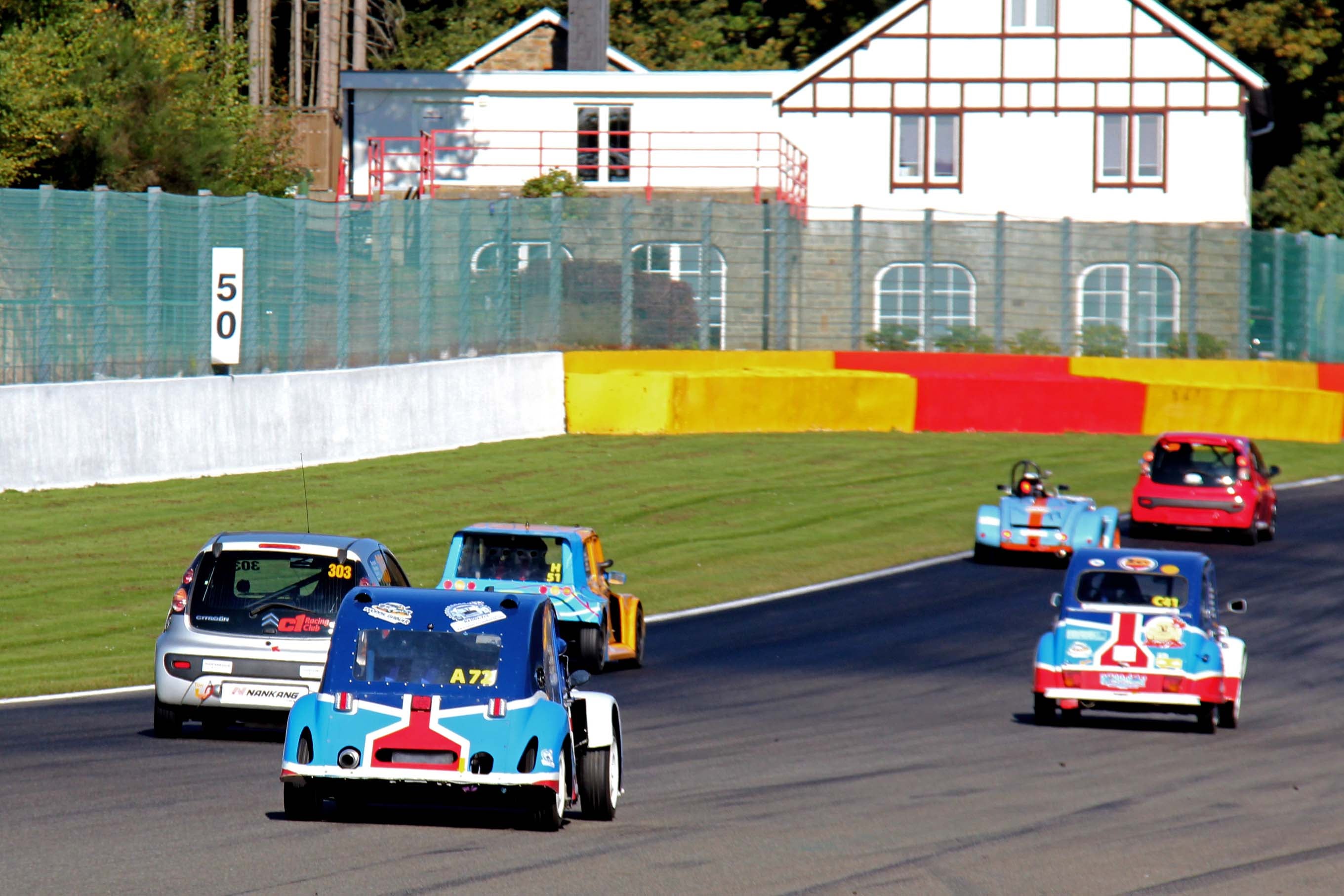

Taking over the car at the end of a safety car stint, I was immediately launched into a field of 52 cars all bunched together into a crocodile. The club is stringent on its driver standards and it has thrown out drivers for executing unsafe manoevres, so the racing is – while utterly hectic – also quite clean.

This stint is hard work. Judging where the cars are and trying to keep the car on the perilously slippery track is more nerve-wracking than fun for me, and it takes a good 30 minutes before I begin to relax and gain confidence – take a wider line than usual to find the grip on the sodden track. Let the car slip a bit and use the lift-off oversteer (there’s plenty in these conditions) to pivot the car into corners. Ease the throttle on with painstaking timidity out of corners or you’ll understeer wildly and let that bloke behind you through…

I managed some adequate times but I exited the car after two hours – when a safety car came out again – feeling wrung out and uncertain whether endurance racing was really for me. If it’s this hard in a 68bhp, front-wheel-drive shopping trolley, I couldn’t help but spare a thought for those who were currently pedalling much, much hairier machinery around a wet Nürburgring at the same time. Fun? Hmm. Maybe. It was time for teammate Jason Barron to take over.

Fuel pump pain

The Friday before the race, Reid had noticed that the fuel nozzles – a plastic affair that screw onto the jerry cans – were painfully slow and varied dramatically in effectiveness. So he started testing all of them, with the help of the truly brilliant pit crew (check out XDR Motors in Salisbury if you need a good mechanic or race support). Remarkably, the best nozzle was more than a minute faster at decanting the full jerry can into the car’s fuel tank. How much intense driving would it take to save that much time, for a trick that most of us wouldn’t have thought of?

Sure enough, the fast nozzles were marked up and quietly reserved for our car, although strangely we ended up sharing them with the Priaulx car some 10 hours later… Still, even Reid’s perceptive race prep didn’t save us enough time to make up for my less-than-ballsy racing, so when Barron steered 301 into the night just before 10pm, we were down in 16th.

I’m down for the dawn stint, so it’s time for a nap.

A mild crash

While I sleep for a couple of hours, 301 is involved in a mild shunt and ends up with much of its front bumper being held on with duct tape. We write it down to a bit of weight saving, but being recovered from the gravel costs three laps and lots of time, so we’re down in 32nd by the time I creep back into the garage at around 2am.

Sunlit second stint

Journalist Mark Walton does an ace job of climbing up the ranks during his stint, as the rain eases off and the track begins to dry. Reid’s up next, and I pace, sup coffee and pace a bit more. At some point I have a weird, slightly delirious conversation about exploding penguins, before deciding that what I really need to do is brush my teeth. And drink coffee. And more water, lots of water.

Finally I’m called forward at around 5am. Reid comes in under the safety car, and I’m back out on Rockingham’s International Super Sports Car circuit, heading towards the tight left-hand hairpin that swings you off the speed bowl and into the twisty inner circuit.

There’s a clear dry line appearing, so I stick to it and find loads of grip. With that and the first tint of dawn in the sky, I’m immediately more confident than before and start to gain on cars ahead. Car 301 feels good, turning in well as I trail-brake in. While I still find myself in tight, aggressive packs of cars, I’m confident enough to fight back and hold my own.

In fact, with each lap I feel the racing tunnel vision creeping in. There’s a great overtaking spot if you dive up the inside of Deene – the hairpin running off the bowl. Another if you take a tight line through Gracelands, a fast left-hander that needs just a lift off the throttle to settle the car before you swing in.

Maybe I can get down to a 1:54 rather than the 1:55s that have been my best so far – around three seconds off the fastest times posted.

Next thing I know there’s a car spinning across the bowl in front of me as I’m flat-out in fourth with the car loaded up. I think it’s going to be The End, but somehow – mostly by clenching hard and trying to stay smooth on the brakes and steering – we make it through the melee to live another lap.

The safety car comes out, I check the clock and find I’ve done some two hours. I want to stay out longer but I’ve honestly no clue how much longer the fuel will last and it saves time doing driver changes under the safety car, so I dive into the pits already wanting to head back out again.

Don’t mind the bullies

Cue more sitting around the pits, and eventually I manage to sleep a bit. At some point I ask Reid about why some cars flash their lights aggressively behind you, since I had come out of one such (granted rather rare) altercation only to be miffed to find it wasn’t even a front-runner as I had assumed. ‘It’s just intimidation tactics. Ignore them,’ was the answer.

So there you have another gem. Of course in endurance racing there’s the difficulty of having cars that are laps ahead or indeed laps behind, but the really fast blokes are notable because they never employ those tactics – they just go round you. A touch humiliating, but then learn about their lines and how they make it look so infuriatingly easy by doing your best to keep up.

So stick to your line, and don’t dive wildly around to give somebody else space. Well-intentioned as you may be, it makes you erratic and more difficult to get around. And don’t be intimidated if somebody goes flashing their lights at you. Be courteous, be clean, but also be brave and don’t let them ruin your race.

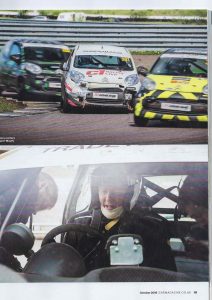

Final stint

1pm. It’s lunchtime and I’m back in the car, desperate for more time on track. We’ve clawed our way back up to 18th, which is quite impressive. Everything feels good, the track is now totally dry, and I’m gunning for a 1:54. I can hardly believe how much confidence I’ve built in this one race.

Confidence has always been my issue when it comes to racing – oddly, I have it in karting but have struggled on the handful of occasions I’ve done ‘proper’ racing of any kind. Yet here I find myself the aggressor on the track. I know I’m faster than plenty of the cars out there and I know where I’m comfortable overtaking.

I spend a deliriously brilliant 30 minutes racing with car 399, which is almost exactly matched to my speed around the track. With this circuit taking in a quarter of Rockingham’s speed bowl, drafting is critical, and I get round him that way. Then he gets by me the same way. I open up a bit of a gap. Then I fluff the entry to the bowl and he’s right back on my bumper. So it continues for I have no idea how long, but it is undoubtedly the finest and happiest racing I’ve ever done. I virtually wanted him to win as much as I wanted us to win by the time my stint was drawing to a close.

And all the time I’m learning how to go round backmarkers, how best to maintain the C1’s momentum (because these are comically slow cars), how best to keep the lap times down and chip away at the field… It is the most remarkable learning curve and the best fun.

Competitive comradeship

Racing can be bitterly, unpleasantly competitive at times. The Citroen C1 Racing Club is not like that – competitive, yes, but also friendly. I had someone give me the thumbs up during an overtaking manoeuvre – it’s that kind of experience, plus the car is slow enough to allow you to do that kind of thing.

Maybe what sums it up best is what happened at the end of the 24-hour race. Around five minutes before the end, car 402 ran out of fuel on School Straight – just ahead of the pits. But he hadn’t run out of luck or friends, since car 318 driven by James Poulton – who had been to-ing and fro-ing with car 402 – took pity and slowed down to give 402 a shove into the pits, where he received further shoves from crews of various garages all the way to his own garage. He managed to get back on to the track to finish the race.

Car 318 actually lost a position in the race (benefitting 301, no less) for his gentlemanliness, but no doubt he got beer enough to make him feel better about it. He also got two points on his licence, but I’m told he’s rather proud of them…

And that’s the sort of stuff that makes the Citroen C1 Racing Club simultaneously a brilliant place for just having fun and also one for seriously working on your racecraft. We finished 14th, which I am heartily chuffed with, especially given how far down we slipped in the middle of the night. Team C’est La Vie in car 349 won the race, and also started on pole, which gives you some idea of how fiendishly rapid the crew of five drivers was.

In truth what I took from it was just how perfect this series is if you want to learn to race better – if you want to learn to race full stop.

I learned how to take time to judge another driver’s style and lines before overaking, I learned strategy, and I had an absolute ball doing it. It’s the perfect balance of unintimidating fun in a race car that’s as easy to drive as they come, mated to low costs, a great field of drivers and some brilliant tracks and good company all round.

If you want to learn to race, start here. Definitely do some track days or karting first, but whatever you do, get into the Citroen C1 Racing Club because it’s the best fun and the best racing, the best bunch of people and the best tuition you could hope for, regardless of the bargain price.

Photos: Marvin Hall Photography

Thanks to the Citroen C1 Racing Club

&width=1600)

&width=600)

&width=600)

&width=600)

&width=600)

&width=600)

&width=600)

&width=600)

&width=600)

&width=600)

&width=600)

&width=600)